Title of Study: “Advancing human gut microbiota research by considering gut transit time”

Published: 28th September, 2022 | Link: View study here | Authors: Nicola Procházková, Gwen Falony, Lars Ove Dragsted, Tine Rask Licht, Jeroen Raes, and Henrik M Roager

In Summary:

- The time it takes for food to pass through the gut is different for everyone

- That’s a big reason why our gut bacteria are different too

- Gut bacteria can also influence the speed food travels through the gut

- Some health problems may be linked to changes in how fast food moves through the gut

Fundamental Findings:

Gut transit time is how long it takes food to pass through our digestive system.

It plays an essential role in shaping the composition of our gut bacteria and activity. Both are connected to our overall health.

Gut transit time varies a lot between people (and even within the same person). These variations affect gut bacteria composition and how they function.

Gut transit time can be divided into three parts:

1) The time it takes for food to leave the stomach

2) The time it takes to travel through the small intestine

3) The time it takes to travel through the large intestine

In healthy people, the total time it takes for food to travel through the whole digestive system can vary a great deal, but the average time is about 28 hours.

Gut transit time can also change within a person over time,. This can affect their health due to changes in the composition of their gut bacteria composition and how they work.

For example, some digestive system diseases like constipation or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) involve changes in gut transit time.

Slow transit through the small intestine may lead to an overgrowth of bacteria, which is often found in people with IBS.

Even different types of IBS can have different gut bacteria compositions, which could be influenced by variations in transit time.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which includes Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, also involves changes in gut transit time and is connected to changes in specific compounds in feces.

Both constipation and IBD can increase the risk of colon cancer, which has been linked to Western-type diets and prolonged gut transit time.

These factors can lead to an imbalance in the types of compounds produced by gut bacteria and may play a role in the development of colon cancer.

Constipation and changes in bowel habits have also been connected to brain and metabolic diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, and obesity.

Changes in gut movement affect how long it takes for nutrients to be absorbed, which may lead to changes in hormone levels and blood sugar control.

Gut transit time can make it harder to study the composition of gut bacteria when comparing different groups of patients. The role of gut transit time in the early development of diseases is still unknown.

Understanding these connections can help us learn more about the relationship between gut bacteria, diet, and disease.

By including gut transit time measurements in studies about gut bacteria, we can improve our understanding of the links between gut bacteria, diet, and disease, which may be important for preventing, diagnosing, and treating various diseases in the gut and beyond.

Study Snapshots

Key Messages:

“Gut transit time varies considerably between and within individuals, and explains large proportions of the gut microbiota compositional variation between people.

Gut transit time affects substrate availability in the colon affecting the trade-off between saccharolytic and proteolytic fermentation.

The gut microbiota can via production of metabolites stimulate gut motility thus affecting the transit time

Many disease-related microbiome signatures may be confounded by alterations in gut transit time.

By considering interindividual and intraindividual differences in transit time in human studies, diet–microbiota interactions and disease-related microbiome signatures may be better elucidated.”

Introduction:

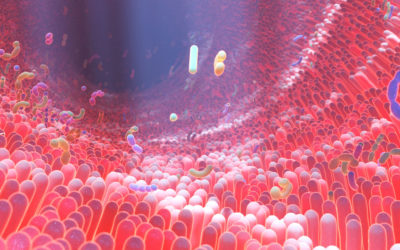

“The human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is densely populated by microbes, which play an important role in a broad range of physiological processes from the digestion of complex polysaccharides to the regulation of neural signalling.

The composition and metabolism of the adult gut microbial communities are affected by a combination of factors including diet, demographics, use of medication, health status and environmental components shaping the gut environment.

Among these environmental components, gut transit time, that is, the time it takes foods to travel through the GIT, appears to be a major driver of gut microbiome variation.

Gut transit time varies markedly between and within individuals and has been associated with gut microbial diversity, composition, and metabolism.

The anatomical segments of the GIT (ie, stomach, small intestine and colon) have segment-specific transit time, affecting the composition of the residing gut microbes.

Although this knowledge is well established, differences in transit time and pH within and between individuals have largely been neglected when investigating person-specific gut microbiota signatures.

Here, we review and discuss the role of gut transit time as a key determinant of the gut microbial composition and metabolism as well as of many diet–microbiota interactions relevant to human health.

We discuss the implications of altered gut transit time in health and disease, and provide an overview of the currently available methods for assessment of gut transit time in humans.

Transit time throughout the GIT:

“In healthy populations, whole gut transit time (WGTT) varies substantially between individuals with a median WGTT of approximately 28 hours.

Segment-specific transit times are commonly referred to as gastric emptying time (GET), small intestinal transit time (SITT) and colonic transit time (CTT). GET is the time it takes for food to empty from the stomach and enter the small intestine in a form of semiliquid chyme.

SITT is the duration time of the passage of the chyme from the duodenum (i.e. the proximal small intestine) until the ileocaecal region, and similarly, CTT corresponds to the duration time of the chyme’s passage from the caecum until the egestion in a form of stool.

For GET of solids, a transit time coefficient of variation of 24.5% has been reported between individuals.

Several human studies have identified large interindividual variation in SITT with a median of approximately 5 hours (range of 2–7.5 hours).

Compared with the small intestine, transit through the colon is much slower with a median of 21 hours.

Consequently, large interindividual variations are often seen in CTT with the minimum and the maximum reported transit times of 0.1–46 hours for the proximal colon, 0.3–80 hours for the distal colon and 1–134 hours for the rectosigmoid colon.

Gut transit time also varies within individuals over time. For example, repeated measurements of CTT using radio-opaque markers within eight healthy subjects over a period of several months showed that each subject exhibited a wide range of CTT with a mean coefficient of variation of 25%.

Furthermore, a recent study showed that the percentage of the faecal water content, a proxy of transit time, varied from day to day in both healthy subjects and patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Similarly, intrasubject differences in SITT and CTT have been observed with tandem measurements in 10 healthy adults using the SmartPill capsule that can directly assess WGTT and segmental transit times.”

0 Comments